Disclaimer, 2023

Having come a long way from the days related herein, I thought for a while before reposting this 26-year-old piece of writing, originally posted on my old website.

I think it has merit as a piece of my own writing and as a remembrance of someone I liked and cared about, despite how difficult he sometimes made it. But now that I'm doing things online under my real name, I do have to stop occasionally and think twice about how some of the less conventional anecdotes from my youth might be misinterpreted. I lead a very quiet life nowadays, but when you do business with people, sometimes you find yourself in an unwanted relationship with someone who loves dirt, reasonable or not, and you'll get painted as a bad guy by certain of those people only because they feel it may profit them to do so. So I had a good hard think about fidelity to some of my most heartfelt creative urges versus a remote but real potential possibility of, ludicrously, someday potentially being made to answer to someone's perhaps motivated and intentionally-distorted account of my character based on an old narrative about who I associated with 3 decades ago. Less logical things have, unfortunately, happened. However, perhaps foolishly, and not entirely consistent with recent experience, I am going to put my faith in the likelihood that truth will out.

I was friends with Hale, the subject of this elegaic recollection, despite his habits, not because of them. My own biggest excess at that age, in those first years following college, other than admittedly often drinking far too much and playing my guitar too loud too late at night, was probably having too much faith in someone who every reasonable person except me easily saw was cruising headlong, with undue haste, towards the inevitable. I suppose at first, when fate checked Hale into the same long-term shared hostel dorm room as me, I was amused, maybe even fascinated, by this unceasing one-man dionysian revel. And then, more due to the close proximity of living communally long-term in a youth hostel than any sort of effort or decision, over time I got to know the good soul in the middle of that cyclone, and it made me willing to overlook a lot. Too much, apparently.

So, to spare myself having to worry about those who might seek to distort anything: I don't endorse the behavior related herein—which should stand to reason, considering where it quickly led—and just because I was friends with the guy shouldn't be read as implying that I myself partook back then in anything outside of that explicitly acknowledged below. At that time of my youth I a little too often fell into searching for salvation at the bottom of a whiskey glass, and could bend an elbow with the best of them, but beyond that, I wasn't anything like the man's peer in that respect. I've always thought there was something to be said for survival, as well as for having a sense of empathy for how my actions might affect those around me, and those beliefs were not only the opposite of everything Haley was about, but also, have only become more durable as I've gotten older.

Nowadays I can't say there's a lot of circumstances where I worry very much about people judging me, especially for who I was friends with 30 years ago, but on the off chance someone is troubled on the basis of this tale and has a reason to actually be concerned by questions of exactly how far past the bounds of respectability and propriety I ever strayed in my reckless 20s (or even now, although nowadays there's nothing to tell,) don't make assumptions—just ask, I'd be happy to tell you.

Ultimately, this stands an account of one long-ago facet of a long and very multifaceted life (and one posted on a website whose terms and conditions, which you should have read, clearly warn you not to assume anything you read here is factual.) It is presented as just that, no more, no less.

( I hate to do this, but this is still the real world: Anyone seeking to take this as anything but an an ancient recollection and work of creative writing, absolutely irrelevant to anything outside of whatever momentary literary enjoyment you get during the act of reading it, should please also remember that your use of this website indicates your agreement to the terms and conditions. )

Sordid past life disclaimed! Enjoy.

One final note: over the years I have gone back and forth on using Haley's real name in this. For a long time after I first posted it I used a pseudonym for him, as I usually do for anyone centrally involved in these kinds of recollections, or who it may not be entirely fair to associate with certain past events I've written about without their permission. In this case, because the essay was so personal, it began to bother me that I had used a fake name, it put the events at a remove from reality, fictionalized the account. And so, a few years after posting it, I made the decision to use his real name instead, although with many other minor identifying details and proper names changed. Now, however, enough time has gone by that not only has Haley's almost entire immediate family passed away, but my own extended family has grown, including a new younger member born over 10 years after the events described herein, with the same given name I have replaced with "Hale", and who is now old enough to find, read, and understand this piece. I have a gut aversion to the thought of that innocent child reading this and feeling any sort of even incidental personal connection or basis for identification with this specter of a time in the past when I myself was not far beyond that age. I feel more convinced that this is right than ever, just now as I sit and write this note. So once again I have changed my friend's name to "Hale", a fictitious one.

—Mike Kupietz, 2023

ARS MORIENDI: HALE'S EPITAPH

Friday, October 3, 1997

On day 73 of my journey, I reached the near frontier of HaleWorld. Donning my pith helmet, I waded out into the tall grasses."

Between the time I first met my friend Haley, almost four years ago, and the time he died, at 1 am yesterday morning, he had alienated the better portion of the people I ever knew him to be acquainted with, as well as gotten himself 86'ed out of almost every decent bar in the city of Seattle. Hale was a larger than life character, a 6' 3" swaggering ball of destructive energy who consistently unsettled and occasionally even scared almost anyone who didn't know him well—especially when he'd been without sleep for about two days and was ambulatory (if not exactly awake) only with the aid of the combination of whatever chemicals he'd come across in his meanderings. Such as he was at 1 am yesterday morning, when the last bartender who ever poured him a drink led him out to the back patio of the last bar he ever drank in.

Hale was a prodigious drunk and a prodigious drug abuser. Most people I knew saw his path through life as little more than a slow motion car crash, and kept their distance from him, not wanting to be around when the wreckage started flying. I was one of a few who believed there was something more than that to Hale—I don't know, I may have been wrong. But since the people who knew him as a friend were far fewer than those who were acquainted with him solely as a spectacle, I wanted to talk about him here.

I remember a few months ago, I can't recall what movie it was, but a few of us were at a midnight screening at the $2 theater—which is a big old place downtown that shows 2nd run movies, a very cool theater. Hale had called me earlier in the evening about getting together. Since nights with Haley usually involved getting blind drunk and spending too much money, and I wasn't in that particular mood, I declined—obsequiously inviting him along to the movie, if he cared to come, knowing inwardly that sitting still in the dark for an hour and a half with attention focused was opposed to everything Hale was about.

So me and five friends were sitting there in the theater, 20 or 30 minutes into the movie, my friends (but not myself) bright eyed and giggly, having sparked up a couple of hoovers right before the flick, when a voice rolls through the darkness: "MICHAEL KUPIETZ."

Five stoned pairs of eyes snapped sideways at me, big as saucers.

"Hale!" I called out.

Five stoned pairs of eyes silently asked, "WHAT—ARE—YOU—DOING?"

And Hale appeared in the aisle, lumbered in front of, over and across five stoned pairs of eyes, big as saucers, and myself, and then all 6'3" of him swayed, tipped over and collapsed at once straight into the seat next to me. The guy in the seat behind yelled, "AAOOWW!!", and jerked his foot back from its resting position against the back of Hale's chair.

Hale turned to me calmly and said, "Hey, dude"—then sat still in the dark, with attention focused, for the remainder of the movie.

AFTER THE MOVIE, we walked over to the Hurricane Cafe—myself and Hale, and my five friends, trailing at a cautious distance and with a wary eye. After we put our name on the waiting list for a table, my friends fell into some sort of stoned negotiations out front, and Hale suggested he and I wait in the bar.

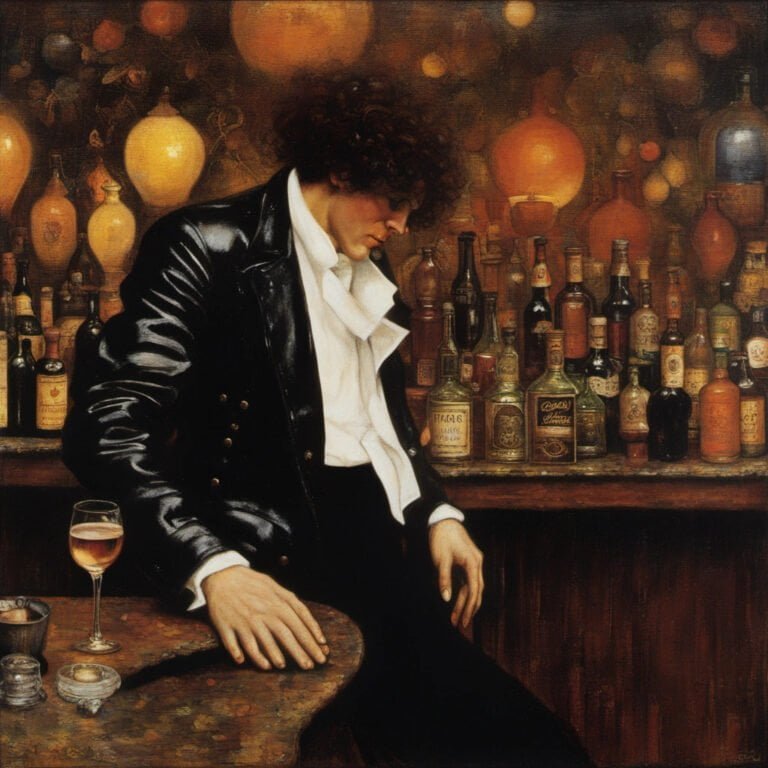

I am at a bit of a loss to convey the character with which Hale the barfly could conduct the ritual of ordering and drinking his liquor. "Drinking on a professional level" was the phrase he always used. As in, "Hale, whatcha doing tonight, man?" "Oh, not much... just drinking on a professional level."

At the bar, Hale cocked an eyebrow at the bartender and delivered a line: "I'd like a Jack and Coke for myself, and a beer for my attorney here" (a nod to Hunter S. Thompson, there; it was something we called each other constantly.) Then, in quick succession:

1.) Bartender puts cocktail glass on bar, in front of Hale, with ice;

2.) Bartender pours Jack Daniels into glass and tops off with Coke;

3.) Bartender turns to get beer glass and beer from the fridge behind him;

4.) Bartender puts glass in front of me and fills to lip with beer; and

5.) Haley slams his empty cocktail glass on counter and says to the bartender, "I'd like another Jack and Coke, please—and one for my attorney here."

The second round came, Hale chugged down his second cocktail, and immediately started eyeing mine—his silent way of saying I wasn't drinking it fast enough—when we hadn't even been there long enough for me to get more than three good draws off my FIRST drink. Just then, one of my friends stuck his head in from the front and said that they had decided they didn't want to eat there after all. I took 2 gulps from my beer, Hale knocked back the Jack and Coke he'd ordered for me in one gulp, and we walked out. Hale eyed me and said, "Mike—you're fired." To which I gave the stock reply—"yeah, we'll see what happens next time you need quality legal representation." Total time to arrive, drain three cocktails, make witty repartee, and leave: less than two and a half minutes.

The above aside, what I really wanted to write about was what happened on the walk home that night. It was a small incident, but for me it illustrates who Haley was—the sort of thing that really sums up what he was like to be with.

Leaving the movie, Hale had told me he was cold sober. I didn't press him for details, but if I had to guess I'd have said at that moment that "cold sober" meant five or six beers and a tab of ecstasy. At any rate, as we walked through Seattle Center fairgrounds he was cogent and collected enough that my friends, though still wary, had at least become comfortable enough to walk side by side with us instead of keeping a safety buffer. The exit from Seattle Center was in sight when we passed a security guard, standing about 30 feet away.

Hale cheerfully called out, "Good evening officer! How are you tonight!" (my friends' eyes opened wide again, fearing—rightly—that the element of chaos was once more about to enter their lives.)

And the guard pleasantly called back: "I'm good. What are you up to?"

Hale again, as cheerfully as possible: "Oh, nothing much—we're just talking about some cum-guzzling ho-bags."

Thirty feet away, the guard's face registered total incomprehension—not of what the words meant, I think, so much as of the fact that they were said at all. "WHAT??"

"Oh, I just said"—big smile here—"we're talking about some cum-guzzling ho-bags!"

And the guard froze for a moment... then broke into a grin and chuckled. "OK! Have a good night!" And we walked home.

A small incident, but it was vintage Haley. Funny, chaotic, crude as hell, a little scary, and, in a unique way, pretty charismatic. That's how I'm always going to remember him.

LISTEN, I WANT TO TELL you the fundamental truth about Hale: He didn't have a malicious bone in his body. Even those who wanted nothing to do with him would concede that fundamentally, he was a good person. "I don't dislike the guy, I just don't want him around" was a sentiment I heard more than once (particularly from any friends who, say, owned or rented any property.) He was witty, ingenuous, and, in his own way, charming. He loved music, and though very few people knew it, he was a quite passable guitarist—his playing was unrefined, but he seemed to have a sensitive ear, and improvised with feeling.

Now, don't get me wrong. In addition to the arguably rational fear he inspired in people simply by being 6'3", lumbering, pale as death, swaggering drunk and clearly wired to the gills, it is a fact that chaos did follow Hale around.

No, it didn't just follow him around—he led it, on a leash. This was the guy who pissed off both me and the friend on whose couch I was staying by pounding on the door at 5 am, waking me up, to offer me some crank—and then justified it by telling me, "Hey, man, I could not think of ANY BETTER thing to do at five in the morning than some high quality methamphetamines!" This is the guy who once showed up at my place and without knocking walked in on me and my girlfriend, smack dab in the middle of sex, then stared stupidly before shutting the door for just long enough to make her uncomfortable (glazed over, I later found out, from over two days without sleep), and then, once she had dressed and left, hit me up for a $30 loan.

I remember once he got into a drunken argument with some unwitting barfly, over a topic which I can't recall but which somehow culminated in him standing up in his seat and bellowing, "EXCUSE ME, SIR, I USE HEROIN—BOTH IN AND OUTSIDE OF CHURCH!", scaring the hell out of rest of the otherwise quiet bar. Even when he wasn't doing anything quite so memorable, Haley the barfly knew nothing of reason or moderation. Not content with just buying you a drink, he'd line up 6 shots of whiskey in front of you—then, when you had finished three of them, would line up 6 more.

Suffice it to say, nothing about Hale was discreet. But for all the chaos, the thoughtlessness, and the occasional carnage he caused, Hale never intentionally targeted the people around him. I believe it was all almost incidental—not destruction aimed at those around him, so much as spillover into his surroundings of destruction aimed primarily at himself.

The magnitude of Haley's self-destructive habits was unbelievable, staggering. In the period of time I lived with him, in the months after we first met, he would frequently come home from a long night, stone drunk, late in the morning—sometimes late in the afternoon. "Dude," he would say, before collapsing, "I'm toast." I once watched him sit for 2 hours, in the small hours of the morning, pale and quaking with coke-induced paranoia of imagined cops lurking behind every corner; then he hopped into a cab at 5:45 am to make opening call at his favorite bar. One night, several months ago, I left him nodding out on heroin on a friend's couch, then later that same night got a voicemail message from him saying he had just been up snorting some speed, and then, when I called the next day, was told by his girlfriend that she last saw him at 8 o'clock that morning dropping ecstasy. All this within the span of 12 hours! Hale seemed philosophically opposed to stopping before the money was all spent and the drugs were all used up—which in some cases was long after the body had fatigued and the intellect dulled.

If any demons haunted Haley, egged him on to his stratospheric heights of excess, I never knew about them. In four years of friendship I never heard him express a doubt or a fear. He never exhibited sadness, alienation or frustration—just a colossal propensity for getting very, very fucked up. Basically, he's left us all, his friends, without ever having given a hint as to why he was so driven to do the things that killed him.

HALE'S BODY WAS FOUND doubled over at the bottom of a stairwell outside his apartment building. In the four months previous he had been to the emergency room twice that I'm aware of, both times complaining about his heart or chest after doing street drugs.

He had been drinking at a bar adjacent to his building's property when he started complaining to the bartender that he couldn't breathe. Paramedics were called. Hale was led to the back patio by the bar staff, who, if things went as they usually did with Hale, were scared by his huge frame and obviously drug-fueled shiftlessness, and wanted first and foremost to get him the hell away from the rest of the customers. I'm told he had been up for two days on cocaine and booze.

That was the last time anyone ever spoke to Hale, so I can only guess as to the reasons for what happened next. Perhaps it was panic. Unable to breathe, he responded to primal fear with a primal thought—escape!—and dug at the dirt under the back fence of the patio. Paranoia must have played a part, some cocaine-induced fear of horrible consequences were he to remain where he was or attempt to exit back through the bar. Either way, he burrowed under the fence, came up into the parking lot of his building, stumbled to an exterior stairwell, fell, doubled over, and died. I consider it a suicide.

He hasn't been gone long enough for me to miss him yet. Past experience has taught me that that will come later, the first time something happens I know he would appreciate, the first time I have something I want to tell him and he won't be there to hear. Right now, I'm so fucking angry at him. I wish he was around for one more day so I could wring his fucking neck.

Hale occasionally talked about going to maritime college in California, and visiting me in San Francisco if I moved there. He wanted to own a bar someday. Shortly before his death, he was offered a job at Boeing, and had landed some high paying salvage work that earned him a couple of grand in a few weeks. He had bought some new shoes and clothes. He was learning to make sushi. I imagined that someday my attorney Hale and I would be 40 or 50, sitting around somewhere laughing about the old days, amazed and jubilant at having somehow survived them.

Ultimately, Hale completely betrayed the faith I placed in him. I defended that son of a bitch to those who belittled him and stood by him as a friend when I could. When he wasn't fucked up he was genial and funny, and a good friend. When everyone else wrote him off as just a drunk drug fiend, a junkie, and nothing more, I was there for the man buried deep underneath whom only I believed was there—and whom I was sure with the support of a good friend would eventually come to the surface so all could see his value as a person. I've never been so fucking let down in my life.

I'd like to think that the drugs weren't what killed him, but were rather a symptom of what killed him. But junkie is as junkie does—or as junkie dies, right? I honestly don't even know. This bleak logic is an attempt to impose sense on the senseless, and in the final analysis all that remains is the simple fact that Hale both lived and died senselessly.

BACK IN THE SUMMER OF '95, Haley invited me to spend a week with his family at their timeshare in Port Aransas, Texas, right on the gulf of Mexico. We spent a week sportfishing and drinking Shiner Bock beer, and I got to see Haley in the unusual context of his family—not Haley the sketchy late-night caller or Haley the swaggering barfly, but Haley the brother and son. A pretty conventional bunch, Hale stuck out like a sore thumb but somehow also fit right in.

Now, when the whole clan got together to fry up the day's catch, it was as loud and noisy a bunch as you'd imagine family of Texans could be, largely due for once not to Haley but to four or five screaming kids which his older sister had brought in tow. There were two or three of her own, plus like one friend each, all between the ages of six and eleven, and hellbent on disrupting whatever reserves of peace or sanity the poor woman could hope to muster. So, you'd try to have a conversation with her, and she was like: "Well, we—KEVIN, STOP PULLING ON THE DRAPES!—anyway, like I was saying, we were—JANEY! DON'T JUMP ON THE COUCH!—anyway..." and so on and so forth.

So, Haley leaves, saying he's gonna get some ice for the drinks. And he's gone, like, 45 minutes... and everyone's wondering, "Where's Hale?" And I'm thinking to myself, Oh, no, Hale, what are you doing this time?

The kids are getting hungry but dinner's not quite ready yet, so they're running around and yelling, there's a Jim Carrey movie on the television, mom's getting exasperated... when back in the door comes Haley. He's holding a brown paper bag. And he proclaims, over the maelstrom, "Hey, Sis,"—now he's got the attention of the whole room—"when I saw your trouble with the kids, I knew exactly what the situation called for."

Everyone quiets down... Hale calls the kids over. Then he opens the bag, and with a huge grin on his face, hands each of the kids a watergun.

That's my attorney. Rest in peace, counselor.