November 27, 2018

I'm staying at my dad's place in Florida right now. I've been on the road for a few months.

It struck me this morning, waking up in Dad's guest room, that this past August I let the 25th anniversary of the day I first quit th' job and hit th' road—August 12, 1993—slip by, unremarked upon.

I realized it today because today is the 25th anniversary of November 27 of that same year, nearly as important a day in my personal canon. I slept the night of November 26, 1993 in my car in a rest area outside of Tacoma, WA, as I'd been doing for the better part of a week, and after my customary free cup of morning coffee courtesy of the local VFW post volunteers at the rest area, I headed over to the Last Exit On Brooklyn cafe in Seattle's University District, as I'd been doing every day for the better part of a week.

Someone down in Yosemite had recommended the Last Exit to me, so I spent a few days hanging out there, meeting people, getting a feel for the town, and waiting for further inspiration to strike. November 27, however, I did something different. Halfway through the day, I had an idea.

Before I left NY in August, one of my stated goals for what I then thought was going to be only a 6-month road trip was to make a pilgrimage to Jimi Hendrix's grave, which I knew to be in Renton, not far from Seattle. So, sitting in the Last Exit on November 27, 1993, I decided that rather than spend another afternoon soaking up the atmosphere there, I'd go out and scratch that goal off the list. I hopped in the car and headed south on I-5 to Renton.

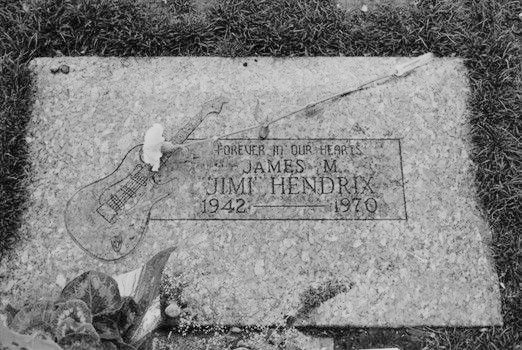

If you visit Greenwood Cemetery in Renton today, Jimi's grave has a massive stone pavilion. Not so in 1993. Before the new memorial was built in 2002, Jimi had a small, flat headstone embedded into the ground, as most gravestones in the cemetery are, that simply had his name, dates, "Forever in our hearts", and a stratocaster guitar engraved into it. You literally could not see it unless you were standing directly over it.

I didn't have a hard time spotting it, though, as a group of people were already standing around it when I got there. For an afternoon I hung out there, talking with fans, drinking a little and occasionally blowing hits of weed into the earth beneath which whatever still remained of Jimi presumably lay.

More people showed up as the afternoon progressed, and a bit of commotion grew.

A nosy guy showed up, asking a lot of people nosy questions. A woman showed up with some small children and lingered around. After a while, I heard her pointing out other graves to the kids. "That's grandma, and that's grandpa."

Eventually a big black car pulled up and a man who must've been in his 70s stepped out, carrying a wreath, and wearing a denim jacket with an incredibly cool black and white painting of Jimi airbrushed on the back panel (remember airbrushed paintings on denim jackets?)

Asking around, I found out what had happened: after months of planning, in the loosest sense, to make a pilgrimage to Jimi's grave, I had, through sheer blind luck, chosen to go on November 27—Jimi's birthday. The nosy guy was a reporter from Musician magazine, there doing a story. The woman with the kids was Janie Hendrix, Jimi's adoptive half-sister. The cool 70-year-old was Al Hendrix, Jimi's father.

Al Hendrix didn't stick around very long. He laid his flowers on the grave, stood in silence for a few, and took off. But everyone else stayed quite a while.

Later on, as the crowd dispersed, I decided to go to my car to get my guitar, and on the way back bumped into Janie Hendrix as she was leaving. We got into quite a long conversation, mostly me grilling her, actually. I asked, "What was he like, not being a rock star, just being your brother, hanging around the house?" I can't recall her specific answer, but it was something about him being a nice guy, and then I do clearly recall she paused and thought for a moment and said, "...but sometimes we thought he was from Mars!"

A few times she seemed to lapse into habitual recitation of things she'd probably said a million times before, like talking about how he died, but that seems understandable, and for the most part we had a pretty good conversation. I finally told her how nice it was of a family member to oblige talking to a fan after this many years, and she said, "Well, we're just glad people still remember."

Many years later at a party I happened to meet a friend of Noel Redding, Jimi's bassist, who was familiar with all the surrounding circumstances, and from him found out that Janie hadn't even really known Jimi well, she was much younger and had only met him a handful of times, but it was a nice conversation anyway. In my mind, I imagine she just kind of wanted to give a fan the experience he was hoping for, and so told me what she knew about him and left out the details that might have diminished the sense of connection.

Later note

(Later note: It should be said at this point that I've since learned more, and Janie Hendrix is considered, perhaps rightly, more of an opportunist than a devoted family member in some ardent Hendrix fan circles, but for purposes of this essay I'm going to stick with what my understanding and impressions were at the time.)

I talked to the reporter for a while too. I looked for the article in Musician Magazine for the next few months but never saw it.

After a while the sun set, and I was alone there. I can't recall specifically, but I probably played a few songs on the guitar. I slipped one of my favorite Tortex purple guitar picks into the dirt beside the stone just to be sentimental. I had brought some charcoal and paper, and before I left made some rubbings of the grave stone as postcards for a few friends, writing on them, "STONE FREE! Greetings from the road, November 27, 1993 —Mike" but they all got stolen from a youth hostel I was living in a few months later, before I'd gotten around to mailing them.

Obviously I stood a few minutes in quiet reflection over the stone, too, and that moment I do still recall with great clarity.

I experienced something in that moment I've experienced before. I've met a few of my idols in person, and it's funny. Sometimes it's really disappointing, because they turn out to be ordinary people. You carry around this mental image, built up over years from repeated music listening, reading interviews, and it's still just a mental image.

Well, I stood over Jimi Hendrix's headstone, alone in the twilight, just me and an inscribed piece of granite, and tried to feel something I thought I should be feeling.

And I only felt one thing: Jimi's not here.

That was the moment I realized, you only get a limited chance. And the images you carry around in your head... well, as they say, the map isn't the territory. Jimi's gone. I didn't meet him. This, what's happening right now, is me looking at a rock, reflecting on something I didn't need to come here to get. Everything else, everything besides this rock, I created in my head. Jimi put it out into the world for people like me to someday receive, but after he did that, he had nothing further to do with it. Any sort of involvement from him is long since over.

There's something to be said for the ritual of paying your respects—I myself have always been uncomfortable with the idea of cremation, I like to think when I meet my end, my remains will be buried and get to have an enduring piece of granite with my name on it as a marker, so people can come pay their respects, or at least strangers might see it and know I existed and wonder who I was—and I'm glad I came to Jimi's grave, for that reason, even aside from the novelty value of serendipitously picking his birthday to do it, getting to meet his close relatives and being interviewed for a music magazine.

But that rock, if my remains wind up under one, won't be me. Nor will the eventual rocks with the names of those I love be them. Once there's a rock, your chance to commune and spend time and appreciate their company is over. The territory is gone, then. All you have is your map of a vanished land.

That was the day I realized a lot of what I imagined I knew were just dreams. Which, together with all this talk of mortality and headstones, may sound depressing, but it's not, at all—it's a reminder to ENGAGE, that the real world is real, and you have to love what's real while you have the opportunity to. And also just realize, sometimes you think something is real, but it's just a phantom you're carrying in your own heart. And that's ok, as long as you know it.

I talked with my dad once about where he would like to be laid to rest. He doesn't care, he feels like death is the end of him and whatever's left doesn't concern him. I envy that a bit. I imagine that after that devastating day I'll drop his ashes in the East River or the Esopus Creek in Phoenicia, NY or some other place that mattered to him, but he doesn't care, himself. I do still have my attachments to phantoms, though.

Forever in my heart.

The below photo isn't mine, I just found it on the internet, because any photos I may have taken of the event are right now under a bed 3000 miles away. 25 years later, to the day, I'm living out of no more than I can carry with me, on the road again—never having completely gotten off it, in my own mind, for better or worse.

Mike Kupietz

On The Road

November 27, 2018